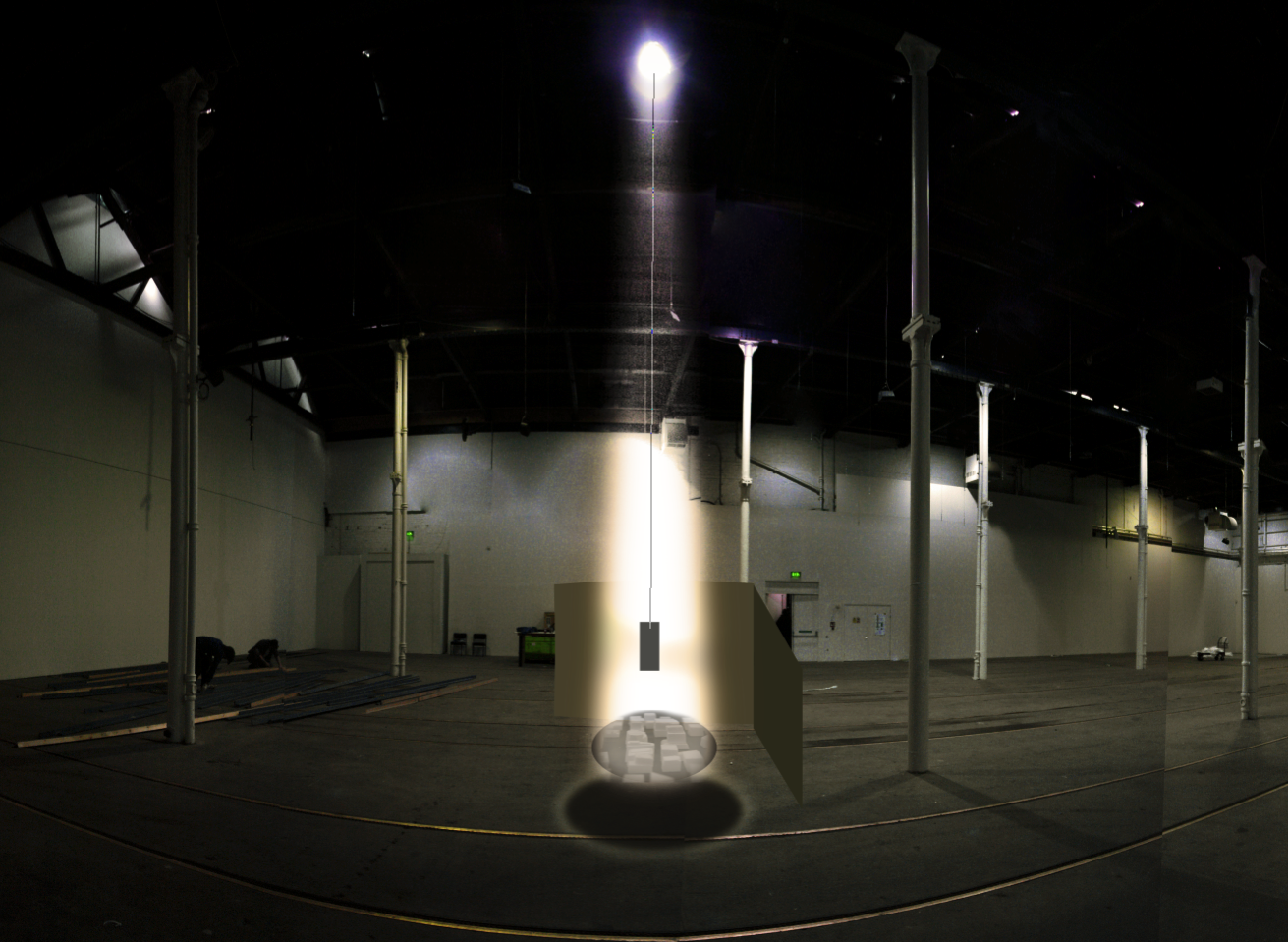

These videos come from a period of studio explorations on the notion of the aerial view, and were preparatory work for an unrealised installation incorporating notions of surveillance and Foucault’s pendulum. With such a pendulum, the inertia of the counterweight resists the rotational force of the earth, which in turn visually effects the elliptical arc of the pendulum’s swing. The background for this exploration was an interest in the democratising effects of newly accessible libraries of aerial satellite imagery, from on-line services such as google earth.

It can be argued that a fascination with high vantage points is a fundamental human trait. Beginning with the obvious strategic advantage a high position provides, the drive is often moralised in the allegories of classic and religious mythology with the folly and hubris of human ambition. In Greek mythologies these traits can be seen in the characters of the artist and innovator Daedalus and the fatal fight of his son Icarus on wings fashioned from wax. In the Near Eastern causation myth of the Tower of Bable found in the first book of the Jewish Tanakh (Genesis), God is provoked to confuse the languages of man to prevent them from completing a tower which would challenge the authority of the heavenly realms.

The democratisation of the aerial view, meaning its wide accessibility to the public, arguably entered the public imagination in force, with the publication of then sensational views taken from a balloon by popular Parisian photographer Nadar in 1858. Years later Nadar’s views were made available for the first time to large numbers of Parisians with the opening of the upper platforms of the Eiffel Tower completed in 1889 for the World’s Fair. The ability to access these views however still remained largely localised, at least in cosmopolitan settings until the development and adoption of improved building techniques and low cost construction steel. These technologies enabled the first truly vertical cities like Chicago and New York. In 1930 New York’s Empire State building was crowned the tallest man made structure, a title it held for 40 years. But it wasn’t until the rapid expansion of commercial air travel after World War II, on the back of wartime innovation and a ready workforce of capable pilots, that the aerial view really began to penetrate into common experience.

A parallel can be drawn between man’s fascination with attaining a high vantage and overall cultural anxiety. In modern times, the very technology that had enabled these dizzying heights brought with it, the world destroying powers of the atomic bomb. After a brief period of jubilation after the end of the Second World War, the anxiety would return in force with Russia’s launch of Sputnik, the first man-made satellite in 1957, just 12 years after the armistice of WWII. Sputnik heralded the beginning of the space race (the US Apollo Space programme ran from 1963 – 1972), and a US-European/Russio-Chinise nuclear arms race, a so called cold war. At the height of the arms race one point of extreme tension was the downing by a Russian missile of US Captain Gary Powers in his U2 high-altitude spy plane in Soviet airspace in 1960. The US viewed arial reconnaissance as vital to both proportional escalation of nuclear capabilities with Russia and averting a potentially devastating confrontation. The U2 incident was a highly public black-eye for the Americans, and it was clear that high altitude recognisance involving the U2 and later SR-71 aircraft were no longer out of reach of Russian missile technology. At this time both nations invested heavily into developing satellite reconnaissance capability, first by ferrying high-resolution analogue films to orbit and back, and later via encrypted radio transmission. By 1970 the the completion of the World Trade Centre’s Twin Towers in lower Manhattan took the title of the world’s highest building, and by 1991 the communist state of the Soviet Union would collapsed. However, with ten years, on September 11, 2001 a new spectre would rise into public view Jihadist terrorism and the destruction of the Twin Towers.

In 2001, Google, was jus an emerging as an internet search giant. Wanting to develop innovative technologies to drive its advertising driven search results in new ways, by 2004 it had acquired the necessary elements for its new ground breaking products Google Earth and Google Maps. For the first time, users could peruse the aerial view on a scale and breadth previously known only to astronauts and intelligence agencies. Unsurprisingly, much of the technology was acquired through the acquisition of other companies. Also unsurprising, yet controversial was the fact that some of these received substantial funding from the Central Intelligence Agency, the primary US agency charged with foreign intelligence gathering and espionage.

Therefore it can be demonstrated that much of the energy driving our present democratisation of the aerial view is the direct offspring of anxiety driven wartime spending and primitively speaking, conceived from the same desires as early man’s want for a safe resting place, with a view.

The films A Rough Sketch for a Proposed Film Dealing with the Powers of Ten and the Relative Size of Things in the Universe, 1968; and later Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero, 1977 by Charles and Ray Eames capture a lighter perspective on the fascination of arial views and man’s relative place in the universe. And though the visual effects and techniques used in the film are more then 40 years old, the films and their message is still remarkably powerful.

Wikipedia Creative Commons

Wikipedia Creative Commons